THE BEAR FACTS

By Dick Wilson

In 1952, I was assigned to the 187th Regimental Combat Team, a part of the 11th Airborne Division stationed in Korea. The 187th was the only paratroop unit to make a combat jump during the Korean War. I wasn’t part of the jump, but Rocky the bear was!

Rocky joined the unit when 1st Sgt. Kendall somehow obtained her from the Hokkaido, Japan, zoo back around 1950. She was just a cub at the time, soon after the unit was ordered to make that combat jump. Having nothing else to do with Rocky, Kendall put her in his kit bag and together they made the jump. At that point, Rocky was promoted from mascot to Private E-1, a full member of the team. Later, she was fitted with her own parachute and eventually made three, non-combat jumps.

Rocky’s career was somewhat checkered. For example, as she grew older Rocky developed a taste for sugar and was known to frequent the mess tent to forage for it. One day, while on such a mission, the mess tent was hit by a mortor shell. Two men were killed and Rocky was injured. At the next morning formation, Rocky was presented with the Purple Heart and promoted to PFC.

But when it came down to it, PFC Rocky was still a bear and bears can get into trouble, especially when given a little help from the boys in the outfit. For example, some time after being injured in the mess tent explosion, some of the boys fed Rocky some booze. Somewhat drunk, Rocky wandered into the 1st Sergeant’s tent and was a bit unruly. Sarge was not amused. At the next morning’s formation, Rocky was demoted back to Private.

Then there were the pranks. One morning, when one of the barracks orderlies had his place all cleaned up and ready for inspection, some of the guys slipped Rocky into the latrine. To Rocky, rolls of toilet paper were toys to be played with — and play with them she did, unrolling many rolls and playing with them on the floor. Needless to say, the barracks didn’t pass inspection.

Then there was the time when a high ranking officer came down from Division and was greeted by Rocky in our HQ tent. Rocky wasn’t happy to see a stranger and chased him around the tent until the guys got control of her. You can bet the Sergeant got an earful!

One time, while I was responsible for watching her, she got loose and was running in the tall grass at the edge of the camp. I grabbed one of the Korean houseboys we called Peanuts and we took off after her. I was wading through the tall grass when, out of the corner of my eye, I saw a brown streak followed by a black one. Then I heard a loud growl mixed with a plea for help. I ran to the scene, found Rocky on top of Peanuts and separated the two. All Peanuts could say was “She tried to eat me!” He took off and I never did see him again.

I said that Rocky had made three non-combat jumps. That’s not to say that she wasn’t performing a useful task. Generally, before we jumped we threw out what we called a wind dummy to let us judge the effect of the wind currents on the jump so we could better hit our target landing zone. On those three jumps, Rocky was our wind dummy.

When the outfit rotated back to the States, Rocky went with them. She was donated to the St. Louis Zoo, where she stayed until her death in 1967.

Rocky joined the unit when 1st Sgt. Kendall somehow obtained her from the Hokkaido, Japan, zoo back around 1950. She was just a cub at the time, soon after the unit was ordered to make that combat jump. Having nothing else to do with Rocky, Kendall put her in his kit bag and together they made the jump. At that point, Rocky was promoted from mascot to Private E-1, a full member of the team. Later, she was fitted with her own parachute and eventually made three, non-combat jumps.

Rocky’s career was somewhat checkered. For example, as she grew older Rocky developed a taste for sugar and was known to frequent the mess tent to forage for it. One day, while on such a mission, the mess tent was hit by a mortor shell. Two men were killed and Rocky was injured. At the next morning formation, Rocky was presented with the Purple Heart and promoted to PFC.

But when it came down to it, PFC Rocky was still a bear and bears can get into trouble, especially when given a little help from the boys in the outfit. For example, some time after being injured in the mess tent explosion, some of the boys fed Rocky some booze. Somewhat drunk, Rocky wandered into the 1st Sergeant’s tent and was a bit unruly. Sarge was not amused. At the next morning’s formation, Rocky was demoted back to Private.

Then there were the pranks. One morning, when one of the barracks orderlies had his place all cleaned up and ready for inspection, some of the guys slipped Rocky into the latrine. To Rocky, rolls of toilet paper were toys to be played with — and play with them she did, unrolling many rolls and playing with them on the floor. Needless to say, the barracks didn’t pass inspection.

Then there was the time when a high ranking officer came down from Division and was greeted by Rocky in our HQ tent. Rocky wasn’t happy to see a stranger and chased him around the tent until the guys got control of her. You can bet the Sergeant got an earful!

One time, while I was responsible for watching her, she got loose and was running in the tall grass at the edge of the camp. I grabbed one of the Korean houseboys we called Peanuts and we took off after her. I was wading through the tall grass when, out of the corner of my eye, I saw a brown streak followed by a black one. Then I heard a loud growl mixed with a plea for help. I ran to the scene, found Rocky on top of Peanuts and separated the two. All Peanuts could say was “She tried to eat me!” He took off and I never did see him again.

I said that Rocky had made three non-combat jumps. That’s not to say that she wasn’t performing a useful task. Generally, before we jumped we threw out what we called a wind dummy to let us judge the effect of the wind currents on the jump so we could better hit our target landing zone. On those three jumps, Rocky was our wind dummy.

When the outfit rotated back to the States, Rocky went with them. She was donated to the St. Louis Zoo, where she stayed until her death in 1967.

THE GRENADE ON DECK

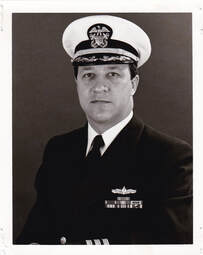

By Bruce Adams

USS Rupertus underway off Vietnam. Note that the "helo nets" on the DASH Flight Deck are in the raised (up) position.

Introduction. USS Rupertus (DD-851) was a Gearing-class destroyer assigned to the US Seventh Fleet, conducting combat missions in Vietnam during the winter of 1970. I was the Gunnery Officer, responsible for the 5”/38 caliber gun battery and other weapons and ammunitions, and was the “WG” Division Officer. As Division Officer, I was responsible for a group og Gunner’s Mates (to operate and maintain the guns) and Fire Control Technicians (who maintained and operated the gun aiming computer systems).

Rupertus was routinely assigned to the ‘Gunline’, usually for one or two weeks at a time. That meant the ship supported Army and Marine units on shore with Naval Gunfire Support (NGFS), using our 5” guns. The guns had a nominal range of 10,000 yards, or about 5 nautical miles. We could fire up to 20 rounds per minute, per gun. So our 4 guns could put out a lot of bullets, and we were always in a high state of readiness to support the troops ashore. During the daytime, we would be close ashore (sometimes less than 1,000 yards) and work with ‘spotters’ who were on the land or, more often, flying in small spotter aircraft. These spotters would call us on the radio for a ‘Fire Mission’, to fire on specific targets. Bullets on demand!

At night, we conducted ‘H & I’ Fire Missions. That was Harassment and Interdiction, when we would shoot at pre-planned targets, sometimes on schedule, and sometimes randomly. The objective was to make the VC feel unsafe as they moved on trails in the jungle at night. They could not feel secure in the jungle, never knowing when a few 5” rounds would drop in on them as they moved about to conduct their business.

It was unclear just who were more “Harassed”, the enemy or the crew of the Rupertus. When we fired our guns, there was shock, noise, shaking and general annoyance aboard our own ship. We tried to keep the night-time firing to just one gun mount, either forward or aft, so at least some of the crew could get some sleep.

On some nights, we would pull into Da Nang harbor, and shoot from there. We entered the harbor before sunset, and would lie-to (i.e., not anchored) in the middle of the large harbor. (While we might have been a “sitting duck”, at least we were not an “anchored duck”!) Da Nang was a large logistics base for Vietnam, and was often under fire from VC rockets or mortars. (Kind of like ‘H & I’ Fire, eh?) When assigned to Da Nang, we would fire on specific targets at specific times, or fire randomly at pre-assigned targets throughout the night. We would usually shoot 100 to 200 rounds per night.

We pulled into Da Nang on one very overcast winter night. The clouds were thick and low, obscuring the hills and mountains which surrounded this beautiful harbor. When daylight was gone, it was total darkness. Our ship was in a darkened condition, showing only normal navigation lights. No white lights were allowed, so that the crew maintained their night vision, and we were hidden in the darkness. And we also threw concussion grenades into the harbor every 15 to 30 minutes, on a random basis. The purpose of the concussion grenades was to discourage any VC from swimming out to our ship and attaching an explosive charge…and blowing us up! Very bad luck to be sunk in the middle of the harbor by a swimmer!

So…in addition to the 5” guns firing ten to twenty ‘random’ rounds each hour, we also threw out ‘random’ concussion grenades, which exploded just off the ship. All of these ‘random’ explosions pretty much meant no sleep for the crew.

Shortly after midnight Rupertus was jarred by a severe explosion, close aboard in the after part of the ship. The Officer of the Deck set General Quarters, and Damage Control reported some minor damage and hull leaks in the after engineering spaces (below the water line). What the heck was that? Were we attacked? Did a successful swimmer attach an explosive mine to the ship?

Here is the story. It took a couple days to reconstruct the facts, but it went like this:

My Chief Gunner’s Mate (GMC Jordan), and his buddy, the Chief Hull Technician (HTC), were out on the main deck after midnight. Chief Jordan went out there (allegedly) to show the HTC how to throw a grenade. (Kind of like kids throwing fire crackers!) They walked aft, inside the ship, then through a door to the main weather deck. The pair proceeded to the after gun mount, where a box of grenades was kept. Chief Jordan would show the HTC how it was done. He took a grenade from the gun mount crew, pulled the pin, and threw it in a high arc, toward the water. (Did I mention that it was very dark and overcast? No moon, not a star, just pitch-black blackness!) The grenade was well thrown, and would have gone 40 or 50 feet…except that the ‘helo-nets’ were down!

The helo nets were a movable set of lifelines on the drone landing deck, above the main deck. The nets were lowered whenever we were conducting replenishment at sea, or drone operations. And they were lowered the day before, and left in the ‘down’ position. And when ‘down’, they acted like a wire mesh awning, over the main deck in the after part of the ship.

So Chief Jordan had pulled the pin and thrown a grenade high in the air. Because it was dark, he didn’t notice the helo nets 6 feet above his head. The wire mesh formed an awning, like a patio cover. He heard the grenade hit the awning, and heard it fall onto the main deck, close to where he and the HTC were standing…in the pitch black darkness. (Did I mention that it was pitch black out on deck?)

The HTC heard the grenade hit the deck, and heard it roll, and then inexplicably reached into the darkness, and grabbed the live grenade. And he tossed the grenade over the lifelines and into the sea. The grenade had a about eight seconds from the time the pin was pulled until it exploded. It promptly exploded when it hit the water, and sent the crew to General Quarters.

Why did the HTC reach into the darkness? Better yet, why was Chief Jordan out on deck? These questions were answered in the usual manner… kind of a non-answer. The Captain wanted an answer, the Weapons Officer (my Boss) demanded an answer, and of course the Executive Officer wanted the details as well. (Fortunately, I was out of the line of fire this time. Despite the fact that they were my guns, my grenades, and my Chief!) (“Ensign Adams, just shut up and pay attention”!)

It became clearer to me the next day. How could this happen? After some reconstruction, the answer was sort of like this: Chief Jordan and the HTC were enjoying an illegal alcoholic beverages in the Chiefs Quarters (appropriately referred to as the ‘Goat Locker’). I can imagine both of them having knocked down a cocktail or two…or five. The HTC was determined to go out on the main deck with Chief Jordan to throw a grenade. And just how surprised were they when it hit the net and bounced down at their feet? But how did the HTC have the presence to reach into the darkness and find the live grenade? And then flip it over the side? Better yet, how drunk where you, Chief, to pick up a live grenade on the deck of a ship in the dark?

All good questions to ponder. Never a dull moment. And just one more Sea Story. Oh…and no repercussions. “Chief, Just don’t ever do that again!” “Aye, Aye, Captain”, said the Gunner’s Mate Chief, with a merry twinkle in his eyes.

Rupertus was routinely assigned to the ‘Gunline’, usually for one or two weeks at a time. That meant the ship supported Army and Marine units on shore with Naval Gunfire Support (NGFS), using our 5” guns. The guns had a nominal range of 10,000 yards, or about 5 nautical miles. We could fire up to 20 rounds per minute, per gun. So our 4 guns could put out a lot of bullets, and we were always in a high state of readiness to support the troops ashore. During the daytime, we would be close ashore (sometimes less than 1,000 yards) and work with ‘spotters’ who were on the land or, more often, flying in small spotter aircraft. These spotters would call us on the radio for a ‘Fire Mission’, to fire on specific targets. Bullets on demand!

At night, we conducted ‘H & I’ Fire Missions. That was Harassment and Interdiction, when we would shoot at pre-planned targets, sometimes on schedule, and sometimes randomly. The objective was to make the VC feel unsafe as they moved on trails in the jungle at night. They could not feel secure in the jungle, never knowing when a few 5” rounds would drop in on them as they moved about to conduct their business.

It was unclear just who were more “Harassed”, the enemy or the crew of the Rupertus. When we fired our guns, there was shock, noise, shaking and general annoyance aboard our own ship. We tried to keep the night-time firing to just one gun mount, either forward or aft, so at least some of the crew could get some sleep.

On some nights, we would pull into Da Nang harbor, and shoot from there. We entered the harbor before sunset, and would lie-to (i.e., not anchored) in the middle of the large harbor. (While we might have been a “sitting duck”, at least we were not an “anchored duck”!) Da Nang was a large logistics base for Vietnam, and was often under fire from VC rockets or mortars. (Kind of like ‘H & I’ Fire, eh?) When assigned to Da Nang, we would fire on specific targets at specific times, or fire randomly at pre-assigned targets throughout the night. We would usually shoot 100 to 200 rounds per night.

We pulled into Da Nang on one very overcast winter night. The clouds were thick and low, obscuring the hills and mountains which surrounded this beautiful harbor. When daylight was gone, it was total darkness. Our ship was in a darkened condition, showing only normal navigation lights. No white lights were allowed, so that the crew maintained their night vision, and we were hidden in the darkness. And we also threw concussion grenades into the harbor every 15 to 30 minutes, on a random basis. The purpose of the concussion grenades was to discourage any VC from swimming out to our ship and attaching an explosive charge…and blowing us up! Very bad luck to be sunk in the middle of the harbor by a swimmer!

So…in addition to the 5” guns firing ten to twenty ‘random’ rounds each hour, we also threw out ‘random’ concussion grenades, which exploded just off the ship. All of these ‘random’ explosions pretty much meant no sleep for the crew.

Shortly after midnight Rupertus was jarred by a severe explosion, close aboard in the after part of the ship. The Officer of the Deck set General Quarters, and Damage Control reported some minor damage and hull leaks in the after engineering spaces (below the water line). What the heck was that? Were we attacked? Did a successful swimmer attach an explosive mine to the ship?

Here is the story. It took a couple days to reconstruct the facts, but it went like this:

My Chief Gunner’s Mate (GMC Jordan), and his buddy, the Chief Hull Technician (HTC), were out on the main deck after midnight. Chief Jordan went out there (allegedly) to show the HTC how to throw a grenade. (Kind of like kids throwing fire crackers!) They walked aft, inside the ship, then through a door to the main weather deck. The pair proceeded to the after gun mount, where a box of grenades was kept. Chief Jordan would show the HTC how it was done. He took a grenade from the gun mount crew, pulled the pin, and threw it in a high arc, toward the water. (Did I mention that it was very dark and overcast? No moon, not a star, just pitch-black blackness!) The grenade was well thrown, and would have gone 40 or 50 feet…except that the ‘helo-nets’ were down!

The helo nets were a movable set of lifelines on the drone landing deck, above the main deck. The nets were lowered whenever we were conducting replenishment at sea, or drone operations. And they were lowered the day before, and left in the ‘down’ position. And when ‘down’, they acted like a wire mesh awning, over the main deck in the after part of the ship.

So Chief Jordan had pulled the pin and thrown a grenade high in the air. Because it was dark, he didn’t notice the helo nets 6 feet above his head. The wire mesh formed an awning, like a patio cover. He heard the grenade hit the awning, and heard it fall onto the main deck, close to where he and the HTC were standing…in the pitch black darkness. (Did I mention that it was pitch black out on deck?)

The HTC heard the grenade hit the deck, and heard it roll, and then inexplicably reached into the darkness, and grabbed the live grenade. And he tossed the grenade over the lifelines and into the sea. The grenade had a about eight seconds from the time the pin was pulled until it exploded. It promptly exploded when it hit the water, and sent the crew to General Quarters.

Why did the HTC reach into the darkness? Better yet, why was Chief Jordan out on deck? These questions were answered in the usual manner… kind of a non-answer. The Captain wanted an answer, the Weapons Officer (my Boss) demanded an answer, and of course the Executive Officer wanted the details as well. (Fortunately, I was out of the line of fire this time. Despite the fact that they were my guns, my grenades, and my Chief!) (“Ensign Adams, just shut up and pay attention”!)

It became clearer to me the next day. How could this happen? After some reconstruction, the answer was sort of like this: Chief Jordan and the HTC were enjoying an illegal alcoholic beverages in the Chiefs Quarters (appropriately referred to as the ‘Goat Locker’). I can imagine both of them having knocked down a cocktail or two…or five. The HTC was determined to go out on the main deck with Chief Jordan to throw a grenade. And just how surprised were they when it hit the net and bounced down at their feet? But how did the HTC have the presence to reach into the darkness and find the live grenade? And then flip it over the side? Better yet, how drunk where you, Chief, to pick up a live grenade on the deck of a ship in the dark?

All good questions to ponder. Never a dull moment. And just one more Sea Story. Oh…and no repercussions. “Chief, Just don’t ever do that again!” “Aye, Aye, Captain”, said the Gunner’s Mate Chief, with a merry twinkle in his eyes.

THE STEAM BOILER TURBINE

(A Kodiak Tale on Kodiak Waters)

By Dean Otteson

Back in the year of '42

Tony, the sailor, was cruising the ocean blue

Aboard the U.S.S. Dent,

The mighty destroyer went.

Into a sea of fog, snow and cold,

Tony stood his endless watch as told.

He was the engineer and kept the engines running hot,

And he loved the warmth of the steam boiler pot.

When Kodiak Island did appear,

Hopes of a landing was near,

But the waves were high and at 20 below;

The ship iced up and began to slow.

The relentless sea washed across the bow

As the Captain said, “Sailor get my scow,"

A landing we will make,

In a sea as high as the ship will take.

“As Captain of this ship, I must demand,

I will conquer this wretched land.”

Now Tony, as engineer, had to run the gig,

So up on deck he shook a leg.

The waters of Kodiak can take a man,

Like no other waters can.

Life is short for the bold and brave,

And Kodiak waters have put many in their watery grave.

The frigid sea has no remorse for who they take,

And Neptune is always on the wait.

The gig was lowered over the side,

So the Captain could take his ride.

And into the night they fled,

With waves going above their heads.

The coxswain steered the little craft,

While the Captain stood at the aft,

Tony kept the engine running fast,

So the Captain could attend the Captain’s Mass.

Business done, the weather was worse,

And the little craft was about to burst.

Upon the return to the U.S.S. Dent,

Down the ladders went,

The Captain and coxswain did ascend,

While Tony took care of closing a vent.

The gig was bouncing back and forth,

And Tony missed a step,

He feel into the sea, as all above could see,

As the king crab waited for thee.

Tony’s heavy clothes began to make him sink,

And life becomes short for a man in the drink,

His life flashed before his eye, as his clothes pulled him down,

Tony knew he was about to drown.

Then like a snake above, a line entered the sea,

From the man above it was sent to thee,

Who know what a line can do,

To save the life of a Navy crew?

Tony grabbed the line as he began to sink,

His hands clutched with all his strength,

And his mates pulled him to the top,

He thanked God a hell of a lot.

The Captain said, “Sit him on his steam boiler turbine,

And don’t anyone disturb him.”

He was frozen to the bone,

And now he felt he was home.

As the temperature began to rise on his seat,

He could feel the fire’s heat.

Soon his two cheeks turned lobster red, as he said, “No lie,

I thought I was going to die.”

(This poem is based on a true story as told to me by 96-year-old Sun City resident Tony Giuffrida, who spent three years in the Pacific during World War II aboard the U.S.S. Dent DD-116.

Thanks for your service Tony!)

Back in the year of '42

Tony, the sailor, was cruising the ocean blue

Aboard the U.S.S. Dent,

The mighty destroyer went.

Into a sea of fog, snow and cold,

Tony stood his endless watch as told.

He was the engineer and kept the engines running hot,

And he loved the warmth of the steam boiler pot.

When Kodiak Island did appear,

Hopes of a landing was near,

But the waves were high and at 20 below;

The ship iced up and began to slow.

The relentless sea washed across the bow

As the Captain said, “Sailor get my scow,"

A landing we will make,

In a sea as high as the ship will take.

“As Captain of this ship, I must demand,

I will conquer this wretched land.”

Now Tony, as engineer, had to run the gig,

So up on deck he shook a leg.

The waters of Kodiak can take a man,

Like no other waters can.

Life is short for the bold and brave,

And Kodiak waters have put many in their watery grave.

The frigid sea has no remorse for who they take,

And Neptune is always on the wait.

The gig was lowered over the side,

So the Captain could take his ride.

And into the night they fled,

With waves going above their heads.

The coxswain steered the little craft,

While the Captain stood at the aft,

Tony kept the engine running fast,

So the Captain could attend the Captain’s Mass.

Business done, the weather was worse,

And the little craft was about to burst.

Upon the return to the U.S.S. Dent,

Down the ladders went,

The Captain and coxswain did ascend,

While Tony took care of closing a vent.

The gig was bouncing back and forth,

And Tony missed a step,

He feel into the sea, as all above could see,

As the king crab waited for thee.

Tony’s heavy clothes began to make him sink,

And life becomes short for a man in the drink,

His life flashed before his eye, as his clothes pulled him down,

Tony knew he was about to drown.

Then like a snake above, a line entered the sea,

From the man above it was sent to thee,

Who know what a line can do,

To save the life of a Navy crew?

Tony grabbed the line as he began to sink,

His hands clutched with all his strength,

And his mates pulled him to the top,

He thanked God a hell of a lot.

The Captain said, “Sit him on his steam boiler turbine,

And don’t anyone disturb him.”

He was frozen to the bone,

And now he felt he was home.

As the temperature began to rise on his seat,

He could feel the fire’s heat.

Soon his two cheeks turned lobster red, as he said, “No lie,

I thought I was going to die.”

(This poem is based on a true story as told to me by 96-year-old Sun City resident Tony Giuffrida, who spent three years in the Pacific during World War II aboard the U.S.S. Dent DD-116.

Thanks for your service Tony!)

SURE, CHIEF, THE GUN IS UNLOADED

By BRUCE ADAMS

USS RUPERTUS (DD-851). Rupertus was “forward deployed” to Yokosuka, Japan. This was an American Naval base (former Japanese Naval base) near Tokyo. There had been a U.S. Navy destroyer squadron stationed there for many years. The senior sailors on these ships were not unlike those in the book/movie “Sand Pebbles:” While the ships rotated back to the U.S. every two years, many of the senior sailors stayed in Japan, and were re-assigned to the newly arrived ships. Thus we had a very professional and experienced crew, of old fashioned “West Pac” (Western Pacific) sailors. (My chief petty officer, for example, had not been back to the United States in over 12 years.) This also made up for the fact that much of our crew was very young and inexperienced. The Vietnam War was still on and the Navy sailors were primarily volunteers, many of whom joined the sea service to keep from being drafted into the Army and sent to Vietnam. So we had “old” senior West Pac sailors, and a bunch of young kids.

The Vietnam War was still going strong, and these forward deployed destroyers were the closest ships to the war. My ship (USS RUPERTUS) was a WW II destroyer that served in the Vietnam Combat Zone perpetually. We spent lots of time at sea, and conducted destroyer operations every day!

I had the best job on the ship: Gunnery officer. RUPERTUS spent many months on the gun line in Vietnam, firing about 10,000 rounds during my tour as gunnery officer. How good was that! The smell of gunpowder in the morning! I had a great division of very hard working, young sailors: two rated gunner’s mates (GMs) and a collection of hard-working, energetic, motivated young strikers, working to make rate.

Every day at sea generated a sea story. One involved a .50-caliber machine gun. RUPERTUS had just left the combat zone, heading to Hong Kong for a respite from the rigors of combat. My chief gunner’s mate informed me that the machine guns had been stowed for sea. The guns were mounted on the ship’s superstructure when in the combat zone. OK, that is good…stowed in the armory. The armory was located on the main deck, aft. Safe storage, indeed! (What could go wrong?)

A few hours later, Chief Jordan walked into the armory. He looked at the two machine guns mounted in brackets high on the bulkhead and said to a young sailor: “Are you sure that gun is unloaded?”

“Sure, Chief, it’s unloaded,” said Seaman Apprentice Flores. He then reached up and squeezed the trigger.

The sound of the blast was heard throughout the ship. The .50-caliber bullet weighed 114.17 grams and traveled at an initial velocity of about 2,810 feet per second as it headed relentlessly toward the forward part of the ship. The 5.45-inch long projectile traveled parallel to the ship’s center line and was about 7 feet above the deck. But our armory was way aft. The deck of the destroyer rose gently as it approached the bow. The bullet traveled parallel to the sea, but the deck rose continuously toward the bow. The bullet passed through aluminum bulkheads, office spaces, storerooms and workshops along the main deck. As it neared the middle of the ship, it was now about five feet above the deck.

The disbursing officer was in his office on the starboard side of the ship. His name was Karl Mess, and he was preparing for payday. Karl was shuffling through pay records at his file cabinet drawer when the projectile entered his office. It lost initial velocity, having gone through a dozen or more metal bulkheads, but it was still deadly. It tore into his bank of jammed file cabinets, shredding pay records and causing destruction. Karl stood at an opened file drawer and the bullet exploded those records about 18 inches in front of his nose.

I was just leaving the wardroom when I heard the explosion. Not loud, but clearly the sound of a gunshot. I walked into the passageway and headed aft, toward the sound of gunfire. I was unsure of the details of the incident, but I knew my guys were involved. I was surprised by the disbursing officer, face scarlet with rage. He confronted me in the passageway, grabbed my shirt collar, shook me violently, screaming “Your guys are trying to kill me.”

He eventually calmed down, and although my guys definitely tried “to kill him,” they were, happily, unsuccessful. Payday was held, as usual. The weapons officer (my boss) admonished us to be more careful with “unloaded” weapons. And my second-class gunner’s mate would not let the chief back in the armory.

(“It’s all his fault!” he said.) There was no punishment for 17-year-old seaman apprentice Flores, who had just finished two months on the gun line, humping 5-inch projectiles for 20 hours a day. The worst punishment was to let him resume his duties as a gunner’s mate striker.

There is nothing more exciting than a bunch of young sailors in a war zone with all kinds of loaded weapons! Like famous comedienne Gilda Radner said, “It’s always something!”

USS RUPERTUS (DD-851). Rupertus was “forward deployed” to Yokosuka, Japan. This was an American Naval base (former Japanese Naval base) near Tokyo. There had been a U.S. Navy destroyer squadron stationed there for many years. The senior sailors on these ships were not unlike those in the book/movie “Sand Pebbles:” While the ships rotated back to the U.S. every two years, many of the senior sailors stayed in Japan, and were re-assigned to the newly arrived ships. Thus we had a very professional and experienced crew, of old fashioned “West Pac” (Western Pacific) sailors. (My chief petty officer, for example, had not been back to the United States in over 12 years.) This also made up for the fact that much of our crew was very young and inexperienced. The Vietnam War was still on and the Navy sailors were primarily volunteers, many of whom joined the sea service to keep from being drafted into the Army and sent to Vietnam. So we had “old” senior West Pac sailors, and a bunch of young kids.

The Vietnam War was still going strong, and these forward deployed destroyers were the closest ships to the war. My ship (USS RUPERTUS) was a WW II destroyer that served in the Vietnam Combat Zone perpetually. We spent lots of time at sea, and conducted destroyer operations every day!

I had the best job on the ship: Gunnery officer. RUPERTUS spent many months on the gun line in Vietnam, firing about 10,000 rounds during my tour as gunnery officer. How good was that! The smell of gunpowder in the morning! I had a great division of very hard working, young sailors: two rated gunner’s mates (GMs) and a collection of hard-working, energetic, motivated young strikers, working to make rate.

Every day at sea generated a sea story. One involved a .50-caliber machine gun. RUPERTUS had just left the combat zone, heading to Hong Kong for a respite from the rigors of combat. My chief gunner’s mate informed me that the machine guns had been stowed for sea. The guns were mounted on the ship’s superstructure when in the combat zone. OK, that is good…stowed in the armory. The armory was located on the main deck, aft. Safe storage, indeed! (What could go wrong?)

A few hours later, Chief Jordan walked into the armory. He looked at the two machine guns mounted in brackets high on the bulkhead and said to a young sailor: “Are you sure that gun is unloaded?”

“Sure, Chief, it’s unloaded,” said Seaman Apprentice Flores. He then reached up and squeezed the trigger.

The sound of the blast was heard throughout the ship. The .50-caliber bullet weighed 114.17 grams and traveled at an initial velocity of about 2,810 feet per second as it headed relentlessly toward the forward part of the ship. The 5.45-inch long projectile traveled parallel to the ship’s center line and was about 7 feet above the deck. But our armory was way aft. The deck of the destroyer rose gently as it approached the bow. The bullet traveled parallel to the sea, but the deck rose continuously toward the bow. The bullet passed through aluminum bulkheads, office spaces, storerooms and workshops along the main deck. As it neared the middle of the ship, it was now about five feet above the deck.

The disbursing officer was in his office on the starboard side of the ship. His name was Karl Mess, and he was preparing for payday. Karl was shuffling through pay records at his file cabinet drawer when the projectile entered his office. It lost initial velocity, having gone through a dozen or more metal bulkheads, but it was still deadly. It tore into his bank of jammed file cabinets, shredding pay records and causing destruction. Karl stood at an opened file drawer and the bullet exploded those records about 18 inches in front of his nose.

I was just leaving the wardroom when I heard the explosion. Not loud, but clearly the sound of a gunshot. I walked into the passageway and headed aft, toward the sound of gunfire. I was unsure of the details of the incident, but I knew my guys were involved. I was surprised by the disbursing officer, face scarlet with rage. He confronted me in the passageway, grabbed my shirt collar, shook me violently, screaming “Your guys are trying to kill me.”

He eventually calmed down, and although my guys definitely tried “to kill him,” they were, happily, unsuccessful. Payday was held, as usual. The weapons officer (my boss) admonished us to be more careful with “unloaded” weapons. And my second-class gunner’s mate would not let the chief back in the armory.

(“It’s all his fault!” he said.) There was no punishment for 17-year-old seaman apprentice Flores, who had just finished two months on the gun line, humping 5-inch projectiles for 20 hours a day. The worst punishment was to let him resume his duties as a gunner’s mate striker.

There is nothing more exciting than a bunch of young sailors in a war zone with all kinds of loaded weapons! Like famous comedienne Gilda Radner said, “It’s always something!”

USS RUPERTUS (DD-851)